Showing posts with label Phil Solomon. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Phil Solomon. Show all posts

1.4.12

Filmmaker Profiles

5:12 PM

---

BAILLIE, BRUCE

---

BRAKHAGE, STAN

---

BROWN, CARL E.

---

CANTERBURY, KYLE

---

DORSKY, NATHANIEL & HILER, JEROME

---

ELDER, R. BRUCE

---

GEHR, ERNIE

---

JACOBS, KEN & FLO

---

MEKAS, JONAS

Labels:

Andrew Noren,

Bruce Baillie,

Carl E. Brown,

Ernie Gehr,

Jonas Mekas,

Ken Jacobs,

Kyle Canterbury,

Marie Menken,

Michael Snow,

Nathaniel Dorsky,

Phil Solomon,

R. Bruce Elder,

Stan Brakhage

26.3.12

Phil Solomon

3:30 PM

---

---

GENERAL INTRODUCTION:

"Like so many filmmakers of his generation (like Alan Berliner, he studied film-making at the State University of New York at Binghamton in the early 1970s), Phil Solomon has been most interested in recycling films made by others into new works that are distinctly his own. While many filmmakers use recycled cinema as a means for satirizing dimensions of American culture or of mod-ern life in general, Solomon’s approach was, from the beginning, simultaneously lyrical and elegiac. As a student at SUNY-Binghamton, he studied with Ken Jacobs, whose Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969, revised in 1971), which uses rephotography to recycle the 1905 Biograph one-reeler of the same name into a complex and remarkable feature, became an inspiration. Solomon’s films are usually evocations of loss—of love, of time, of security, of life—that sing the beauty of what is gone by means of rhythmic and textural evocations closer to music and poetry than to most film.

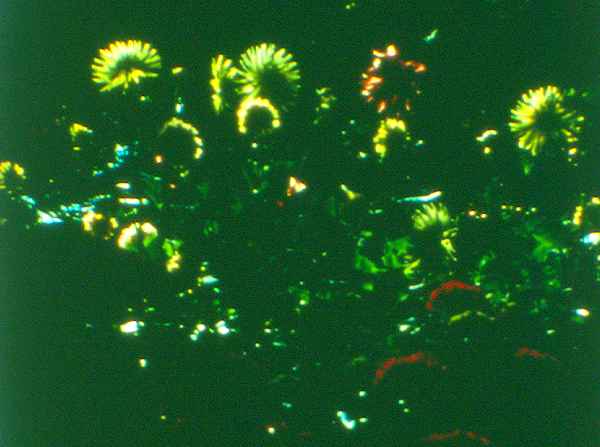

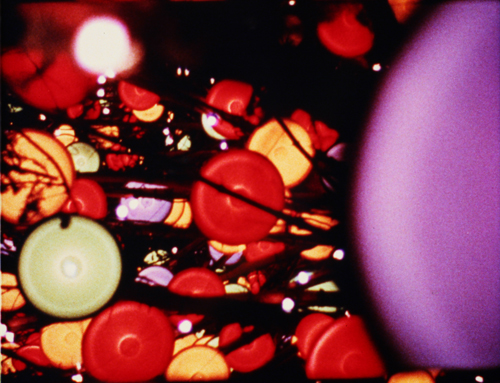

Since leaving the Massachusetts College of Art in 1980 with an MFA, Solomon has explored the literal substance of film imagery with the optical printer, learning to tease emotional resonance frame by frame from the found materials he works on by means of a wide variety of optical and chemical manipulations. The resulting films can easily be read as elegies for the lives originally encoded on the celluloid, and for cinema itself. 'Remains to Be Seen' (Super-8mm version, 1989; 16mm version, 1994) and 'The Exquisite Hour' (Super-8mm version, 1989; 16mm version, 1994) are particularly good examples. Both films present a series of visually ambiguous but texturally astonishing sequences in which imagery is just barely identifiable. Often, we know basically what we’re looking at—a person riding a bicycle, a landscape, a merry-go-round—but can no longer identify its original context. By means of suggestive sound and editing, however, Solomon invests this disparate imagery with a particular emotional tonality.

In 'Remains to Be Seen', the most pervasive metaphor is of a person in an operating room: the sights and sounds of the operating room are motifs that suggest the precariousness both of the person being operated on and, by implication, of the film image and Cinema itself: it “remains to be seen” how long “the patient” will survive. In 'The Exquisite Hour', the statement on the sound track by an old man struggling to come to terms with the loss of his partner (“I’ll never get over it, never”) serves as the (broken) heart of the film, which evokes a variety of forms of cinema—early cinema, home movies, depictions of nature—all of which, like the medium itself, seem to be slipping away, despite what the loss means to us.

Solomon’s films are unusually open to interpretation; they are less about creating particular meanings than about providing evocative experiences that reward the eye and invite emotional engagement. They are aimed not so much at audiences as at the solitary viewer in an audience who can feel the filmmaker’s commitment to the slow, solitary process that produces these films. At times, Solomon has collaborated with other filmmakers—with Stan Brakhage on 'Elementary Phrases'(1994), 'Concrescence' (1996), 'Alternating Currents'(1999), and 'Seasons' (2002); with Ken Jacobs on 'Bi-temporal Vision: The Sea' (1995)—but his most impressive and memorable films are solitary enterprises, especially 'The Secret Garden' (1988), 'Remains to Be Seen', 'The Exquisite Hour', 'Clepsydra' (1992), and the series of 'Twilight Psalms' he has made since 1999: 'Walking Distance' (1999), 'Night of the Meek' (2002), and 'The Lateness of the Hour' (2003). " (Scott MacDonald in A Critical Cinema 5)

Since leaving the Massachusetts College of Art in 1980 with an MFA, Solomon has explored the literal substance of film imagery with the optical printer, learning to tease emotional resonance frame by frame from the found materials he works on by means of a wide variety of optical and chemical manipulations. The resulting films can easily be read as elegies for the lives originally encoded on the celluloid, and for cinema itself. 'Remains to Be Seen' (Super-8mm version, 1989; 16mm version, 1994) and 'The Exquisite Hour' (Super-8mm version, 1989; 16mm version, 1994) are particularly good examples. Both films present a series of visually ambiguous but texturally astonishing sequences in which imagery is just barely identifiable. Often, we know basically what we’re looking at—a person riding a bicycle, a landscape, a merry-go-round—but can no longer identify its original context. By means of suggestive sound and editing, however, Solomon invests this disparate imagery with a particular emotional tonality.

In 'Remains to Be Seen', the most pervasive metaphor is of a person in an operating room: the sights and sounds of the operating room are motifs that suggest the precariousness both of the person being operated on and, by implication, of the film image and Cinema itself: it “remains to be seen” how long “the patient” will survive. In 'The Exquisite Hour', the statement on the sound track by an old man struggling to come to terms with the loss of his partner (“I’ll never get over it, never”) serves as the (broken) heart of the film, which evokes a variety of forms of cinema—early cinema, home movies, depictions of nature—all of which, like the medium itself, seem to be slipping away, despite what the loss means to us.

Solomon’s films are unusually open to interpretation; they are less about creating particular meanings than about providing evocative experiences that reward the eye and invite emotional engagement. They are aimed not so much at audiences as at the solitary viewer in an audience who can feel the filmmaker’s commitment to the slow, solitary process that produces these films. At times, Solomon has collaborated with other filmmakers—with Stan Brakhage on 'Elementary Phrases'(1994), 'Concrescence' (1996), 'Alternating Currents'(1999), and 'Seasons' (2002); with Ken Jacobs on 'Bi-temporal Vision: The Sea' (1995)—but his most impressive and memorable films are solitary enterprises, especially 'The Secret Garden' (1988), 'Remains to Be Seen', 'The Exquisite Hour', 'Clepsydra' (1992), and the series of 'Twilight Psalms' he has made since 1999: 'Walking Distance' (1999), 'Night of the Meek' (2002), and 'The Lateness of the Hour' (2003). " (Scott MacDonald in A Critical Cinema 5)

"Solomon has worked in video before, but the works that established his reputation--as both an image alchemist and a master conjurer of plangent, all-enveloping moods--are so intimately bound to the specific properties of celluloid and emulsion that the shock upon seeing these new works cannot be overstated. While many established experimental filmmakers have turned to digital imagemaking in recent years, for any number of reasons, too few have been willing to dive headlong into the specific, often strange aesthetic character of their adopted medium. But 'Untitled' and 'Rehearsals' are so thoroughly immersed in the texture and atmosphere of digital gaming that I wasn’t initially certain how to access them. Unlike Solomon’s previous films, works that engaged in abstraction but were nevertheless tied to the concrete indexical character of photography, these new pieces explore the possibilities of a very dark, very foreign world." (Michael Sicinski)

---

FILMOGRAPHY:

Night Light (1975)

The Passage of the Bride (1978)

The Passage of the Bride (1978)

As If We (1980)

Nocturne (1980)

What’s Out Tonight Is Lost (1983)

Nocturne (1980)

What’s Out Tonight Is Lost (1983)

The Secret Garden (1988)

The Exquisite Hour (1989)

Remains to Be Seen (1989)

Rocket Boy vs. Brakhage (1989)

Clepsydra (1992)

Elementary Phrases (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (1994)

The Exquisite Hour (1994)

Remains to Be Seen (1994)

The Snowman (1995)

Concrescence (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (1996)

Alternating Currents (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (1999)

Twilight Psalm II: Walking Distance (1999)

Yes I Said Yes I Will Yes (1999)

Innocence and Despair (2001)

Seasons . . . (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (2002)

Twilight Psalm III: Night of the Meek (2002)

Twilight Psalm I: The Lateness of the Hour (2003)

Remains to Be Seen (1989)

Rocket Boy vs. Brakhage (1989)

Clepsydra (1992)

Elementary Phrases (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (1994)

The Exquisite Hour (1994)

Remains to Be Seen (1994)

The Snowman (1995)

Concrescence (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (1996)

Alternating Currents (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (1999)

Twilight Psalm II: Walking Distance (1999)

Yes I Said Yes I Will Yes (1999)

Innocence and Despair (2001)

Seasons . . . (co-made with Stan Brakhage) (2002)

Twilight Psalm III: Night of the Meek (2002)

Twilight Psalm I: The Lateness of the Hour (2003)

Crossroad (co-made with Mark LaPore) (2005)

Rehearsals for Retirement (2007)

Last Days in a Lonely Place (2008)

Still Raining, Still Dreaming (2009)

American Falls (2010)

Empire (2012)

Simply Because You're Near Me (2013)

Twilight Psalm IV: Valley of the Shadow (2014)

Empire (2012)

Simply Because You're Near Me (2013)

Twilight Psalm IV: Valley of the Shadow (2014)

---

---

WRITINGS ON SOLOMON:

An Artist Who Inspires New Ways of Seeing by Manohla Dargis

by Michael Sicinski

Last Days in a Lonely Place review by Michael Sicinski

American Falls review by Michael Sicinski

Songs of Solomon by David Accomazzo

Last Days in a Lonely Place review by Michael Sicinski

American Falls review by Michael Sicinski

Songs of Solomon by David Accomazzo

Towards a Minor Cinema by Tom Gunning

Poetry in Motion by Tony Pipolo

by Rebecca Laurence

Epic, eleagaic films by Phil Solomon by Leah Ollman

Invisible Cities by Genevieve Yue

Epic, eleagaic films by Phil Solomon by Leah Ollman

Invisible Cities by Genevieve Yue

The Films of Phil Solomon by Bret McCabe

American Falls-Phil Solomon by CINESPLOSION

In Memoriam Trilogy review by Patrick Friel

Darkness On the Edge of Town... by John P. Powers

Rehearsals for Retirement & Last Days in a Lonely Place reviews

by Genevieve Yue

Bad Lit profile page

Experimental Cinema wiki page

In Memoriam Trilogy review by Patrick Friel

Darkness On the Edge of Town... by John P. Powers

Rehearsals for Retirement & Last Days in a Lonely Place reviews

by Genevieve Yue

Bad Lit profile page

Experimental Cinema wiki page

---

Reflections On the Avant-Garde Experience:

A Meditation on Phil Solomon's The Secret Garden

by Dana Anderson (from Millennium Film Journal 39/40):

---

Found Footage, On Location: Phil Solomon's Last Days in a Lonely Place

by Gregg Biermann & Sarah Markgraf (from Millenium Film Journal 52):

---

"The first is Phil Solomon, who in the process of working with photographed imagery a frame at a time, not painting but using chemicals to crystallize into various shapes minute patters along the line of his step-printing, has, like Gunvor Nelson, also created a counterbalance to what could become sentimental and nostalgic" (Stan Brakhage)

"Solomon has evolved his technique so that in his latest work ('Clepsydra' - 'waterclock') the textures are constantly changing and are often appropriate to each figure in metaphoric interplay with each figure's gestural (symbolic) movement. He has, thus, created consonance with thought as destroyer/creator - a Kali-like aesthetic 'There is a light at the end of the tunnel' (Romantic); and it is a train coming straight at us: ... (and, to balance such, perhaps, with a touch of Zen) ... it is beautiful!" (Stan Brakhage)

"Solomon has evolved his technique so that in his latest work ('Clepsydra' - 'waterclock') the textures are constantly changing and are often appropriate to each figure in metaphoric interplay with each figure's gestural (symbolic) movement. He has, thus, created consonance with thought as destroyer/creator - a Kali-like aesthetic 'There is a light at the end of the tunnel' (Romantic); and it is a train coming straight at us: ... (and, to balance such, perhaps, with a touch of Zen) ... it is beautiful!" (Stan Brakhage)

---

---

WRITINGS BY SOLOMON:

---

A Remembrance for Stan Brakhage:

---

---

PHIL SOLOMON ON FILM:

---

---

INTERVIEWS:

A Critical Cinema 5

Mediating the American Idea: A Conversation with Phil Solomon

Phil Solomon's Historic Film Experiments

Mediating the American Idea: A Conversation with Phil Solomon

Phil Solomon's Historic Film Experiments

---

”But now you have meta-ironies piling atop each other, ad-infinitum. Enough. The most difficult challenge for young artists today is to achieve any kind of earned sincerity or a true sense of the authentic in this horribly cynical, maddening time of multi-layered facades, remakes, and ever present duplicity on a global scale. And what do we call the Grand Canyon when kids refer to their lunch as 'awesome'”? (Phil Solomon)

(and of course, still going strong; this post will be updated accordingly...)

---

Labels:

Phil Solomon

|

4

comments

17.9.10

Carl Brown Interview

8:49 PM

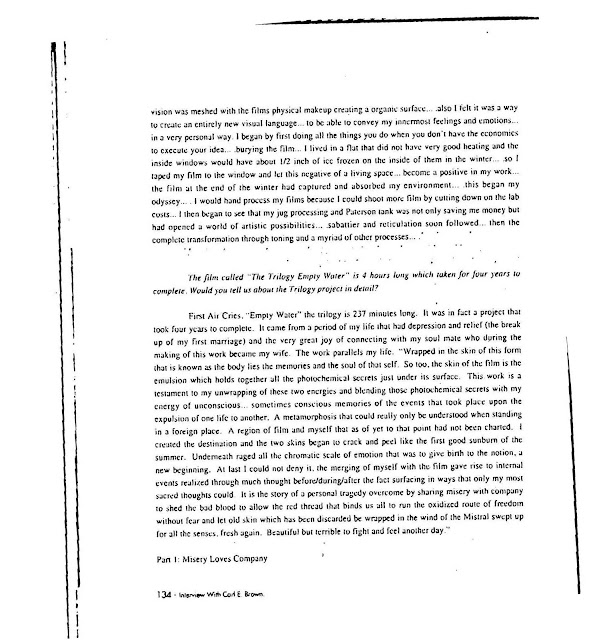

The exile of many of the greatest artists to the margins of their given medium is obviously nothing new, yet the sting that accompanies the knowledge of the occurrence of this injustice remains as vexatious as ever, none more so than in the case of the Canadian artist Carl Brown, one of cinema's greatest visual alchemists. The following interview was included in a small bi-lingual book released on Brown, edited by Hangjun Lee and Gyejoong Kim...

---

Labels:

Carl Brown,

Cecile Fontaine,

Diamanda Galas,

Empty Water Air Cries Trilogy,

Gyejoong Kim,

Hangjun Lee,

John Kamevaar,

Jurgen Reble,

Memory Fade,

Michael Snow,

Phil Solomon

|

0

comments

2.4.10

Brakhage Symposium 2010 Recap

3:03 PM

(better late then never.....then again perhaps not....I won't make any guarantees, but I've been told if you blink rapidly while reading the following prose it will appear less stilted than it actually is....)

Several weekends ago at the University of Colorado in Boulder, the university Stan Brakhage taught at for many years and one of the handful of experimental filmmaking havens around the country, held the sixth annual incarnation of the Brakhage Symposium. Centered around two programs of differing approaches stretched across three lengthy yet wondrous days, one by Ed Halter and the other by Christina Battle and Jennifer Peterson, the symposium presented a collaborative gathering of those involved with the field in various capacities to celebrate and explore the continuing legacy of one of the greatest of all light poets.

The inaugural program, entitled "Repetition, Remaking and Reuse" by Ed Halter, sought to explore the underlying question of what it means to repeat (in aesthetic rather than pathological context). Kicking off with a performance of Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music in which four microphones hang directly above their respective speakers and subsequently are left to swing in a pendulum motion creating a panoply of rhythmically alternating feedback pulses, the keynote address by Annette Michelson quickly established the engagingly heady tone that would permeate the first two days. Michelson, whose essay Camera Lucida/Camera Obscura remains one of the most significant texts on Brakhage’s editing theory and of whom Brakhage praised as “one of the great prose writers of our time…who is able to make language be both specific and metaphorical at the same time”, focused her lecture on what she termed the ‘savage thought’ of both Brakhage and Michael Snow with regards to their cinematic treatment of spacio-temporality. Highlighting a line starting with Rene Claire’s 1925 film The Crazy Ray, she posited the development of various modes of temporal cinematic control (i.e. slow-motion, reverse-action, etc.) as a means of reinforcing pedagogical strength and introducing inherent humor, both naturally positive products. Conversely, such a development also had the possibility of giving the maker a false sense controlling causality and fulfilling their infantile fantasy of omnipotence. She noted that while both men seemingly took diametrically opposed approaches to the subject (Brakhage’s rapid fragmentation merging memory and anticipation into a continuous ecstatic present, Snow concentrating on distending expectation into a purely temporal experience), each were united by their near absolute disregard for what had come to be the dominant treatment of narrative driven production and a desire to undercut the aforementioned phenomenon. This line was further reinforced with the projection of both an excerpt of Brakhage’s seminal 1958 film Anticipation of the Night and Michael Snow’s One Second in Montreal, his musically informed mediation on the collision of still and moving images involving unspectacular photographs in and around the city.

(Michael Snow)

[tossing and turning in the back seat of the car, in my head a door opens, closes and then opens again]

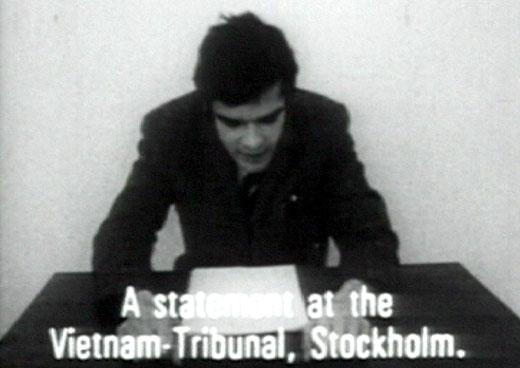

(Inextinguishable Fire by Harun Farocki)

Day two began with a presentation on German Filmmaker Harun Farocki entitled “Blind Faith: Harun Farocki Envisions War” by David Joselit. Delivered with a clear and confident precision, Joselit explored Farocki’s ‘doublesness of vision’ (inner and outer/technology of war and technology of peace, etc.) in two of his works, his 1969 film work entitled Inextinguishable Fire and his more recent digital instillation piece (utilizing double projection) entitled Immersion. This ‘doubleness’ took hold in the works in three ways. First as conflict between consuming and witnessing. In Inextinguishable Fire the lesser act of consumption undermined through repetition depicted by the monotone reading of a victim’s account of the devastating effects of napalm, opposed with the more involved and responsive act of witnessing depicted by Farocki burning his own arm with a cigarette. Second as analytic vision and synthesized vision, the analytic only seeing parts of the whole, thereby disowning responsibility and creating unexpected results once synthesized vision is enacted. Lastly as action and reenactment, exemplified in Immersion by soldiers virtually re-experiencing traumatic wartime situations with therapeutically inclined software (the fact, though not indicated directly by the instillation itself, that the very same software is used to train soldiers for combat AND entertain gamers on their couch presents a potently tragic irony, and further reinforces the idea of the analytic and synthetic visions).

(Peter Roehr)

After a brief interim Halter then presented a program of films by a variety of artists in which repetition was used in a distinct and diverse manner. In his introduction Halter made a point of linking the idea of repetition with the development of machine technology and in that spirit included works produced on a variety of technologies (i.e. 16mm, video, etc.). Among the programs highlights were Peter Roehr’s rarely seen Filmmontages, in which a single brief passage of assorted marketing footage is shown repeatedly, creating a sort of hypnotic reverie that transcends the otherwise mundane subject matter.

(Shulie by Elisabeth Subrin)

Next, Brooklyn based Elisabeth Subrin presented and discussed three works: the dual-channel instillation Lost Tribes and Promised Lands, her seminal 1997 film Shulie and the double projection Sweet Ruin. Throughout each one found past and present gently merging in an elusively lucid dialogue with time and our inability to control it. Examining repetition as an integral component of memory, both Lost Tribes… and Shulie’s shot for shot reconstruction fashioned a fascinating temporal and perceptual dialectic that played out in a remarkably subtle and somewhat haunting manner (indeed it wasn’t until after I had returned that the full impact of Shulie hit home). Perhaps described best by Subrin herself, in various ways each work exposed “edges that call out for a completion that can never be.”

(Andrew Lampert)

The second day came to a close with what turned out to be one of the great highlights of the weekend, two unscheduled 8mm projector performances by filmmaker and Anthology Archives preservationist Andrew Lampert (All Magic Sands, the performance originally scheduled, was foregone due to its complex projection requirements). Ushered in with a very relaxed and inviting air (audience members were encouraged to speak at will) the two revealed the intimate and unassuming possibilities of the small-gauge format. Lampert spoke of his performance work as being 'contracted cinema' (as opposed to the commonly used phrase 'expanded cinema'), one in which he wishes to be personally invested, “feeling it, not running it.” Blurring the illusionary boundaries between amateur and art that would come to be the focus of the Symposium’s final day, the work brought forth a warm humor all too frequently missing from these events.

[turning and tossing in the back seat of the car, wondering if my memories are all edited in-camera]

The third and final day, featuring Christina Battle and Jennifer Peterson’s program entitled “The Amateur and Avant-Garde”, sought to explore the problematic misconceptions surrounding the amateur mode of filmmaking and what is considered more vaunted forms of film art. Continuing in much the same line of communal interaction as the previous night’s performances, Lynne Kirste presented (in the true form of the word, offering interesting tidbits and answering questions throughout) a collection of home movies from the Academy Film Archive largely featuring well-known figures of the professional film industry. Of particular interest were three works from the Alfred Hitchcock collection shot in Lenticular color, which produced an often breathtaking and unexpected shifting color palette.

(I...Dreaming by Stan Brakhage)

Phil Solomon, one of the preeminent living film artists and a close friend/collaborator with Brakhage during his later years at CU, supplied another great highlight with his brief program consisting of a few of the more intimate Brakhage films (a portion of the Songs on 8mm , Star Garden and I…Dreaming on 16 mm), as well as some of his own private home movie footage and his 1995 film The Snowman. The private footage, with live narration by Solomon, offered a rare and poignant look into the origins of some of the themes running throughout his exquisite oeuvre. After the program finished, I was again left wondering exactly what that one ephemeral aspect that accompanies the projection of these works on film was. I’m not sure it is describable, but it is most certainly something potent, something that must be preserved for others to experience (…or perhaps we should just embrace it while we still can, as Phil said before wrapping things up “if this is the end of cinema, let’s dance”).

(The Snowman by Phil Solomon)

Lynne Kirste and Andrew Lampert then sat down to field questions from the audience and speak a little bit about their experiences with archiving and the themes that had been presented throughout the day. It was during this time that an interesting dialectic arose surrounding the nature of the home movie. On the one hand it was Kirste’s experience that many of the home movies she handled offered revealing personal glimpses of moments that would never otherwise be shown in a more professional context. On the other Elizabeth Subrin pointed out that the large majority of home movies exhibited an extremely conventional and clichéd form. For her, it was as much about what is usually not shown and the reasoning behind such decisions as it was what we are actually privy to.

(Erinnerungen [Memories] by Sylvia Schedelbauer)

The concluding program, entitled “An Archive of Memory”, featured works by artists dealing with the many complexities surrounding the memory and its relationship to the moving image, including two works by Sylvia Schedelbauer, who was on hand to discuss her multifaceted approach afterwards. Born of a German father and Japanese mother, Schedelbauer’s work explored the oscillating memorial divisions of her multiethnic heritage in manner at once intensely personal and modestly universal. Comprised largely of both found footage/images and audio, her work was a tender reminder of the artist’s ability to create something lasting out of the most commonplace materials.

After a brief final panel the three-day Symposium came to a close. As a whole the Symposium stood as a compelling reminder of the endless possibilities that still exist in this vast universe of experimental film , one that will by all accounts continue to act as a light for all those intrepid explorers willing to brave its many unknown expanses.

(((The experience was not yet over, in fact perhaps the greatest highlight still awaited the following night in the form of the Vancouver Island Quartet, but that is a story for another day….)))

(A Child's Garden and the Serious Sea by Stan Brakhage, the first film in the Vancouver Island Quartet, courtesy of Fred Camper)

Labels:

Andrew Lampert,

Annette Michelson,

Brakhage Symposium,

Christina Battle,

Ed Halter,

Elisabeth Subrin,

Jennifer Peterson,

Lynne Kirste,

Michael Snow,

Phil Solomon,

Rene Clair,

Sylvia Schedelbauer

|

3

comments

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

(

(